Project Description

Vento di Zeri

Vento di Zeri

Where it is

Villages scattered through the valleys, the silence of the mountains, accompanied by breath-taking landscapes, the rhythms of a bygone life and bizarre local stories. Climbing the road from Pontremoli to Zeri, in the upper Lunigiana, where chestnut forests slowly give way to beech woods as you go higher, you have the sensation of entering a mysterious land, where even the regional identity, quite strong elsewhere, becomes increasingly less so. What’s more, the village, as maintained by the oldest inhabitants here, does not exist.

It is a collective name, that would not be out of place as a title in the collective works of the Wu Ming writers. It is actually a series of small localities, each with its own story, that together makes up a sort of dislocated municipality that has always kept its native character, due to its inaccessible geographical position, nestling in three valleys (Giordana, Rossano, Adelano) and surrounded by Liguria and Emilia. “Zeri eats its own bread and dresses in its own skin”, it was once said, to underline its autarchical economic situation. Grain, chestnut flour, and livestock breeding. Except for a bit of tourism, it hasn’t changed much since then.

| Legend |

|---|

Wind Farm Wind Farm |

Browse the map and discover the places to visit, where to eat and where to stay, chosen by Legambiente

Trails and hiking trails

The typical Apennine features of Zeri make it a perfect place for walkers. With an infinite series of splendid trails, many dating from medieval times, also suitable for mountain bikes. Taking the road that arrives at the Rastrello Pass, which marks the border with Liguria and the Alta Val di Vara, you can join one of the stretches of the Alta Via dei Monti Liguri (AVMl), the 430 kilometre route linking the extreme ends of the Liguria Riviera, from Ventimiglia to the province La Spezia. In this part of the trail, the Alta Via more or less faithfully follows the ancient “Via Regia”, the main trade route in the past linking Emilia, Tuscany and Liguria.

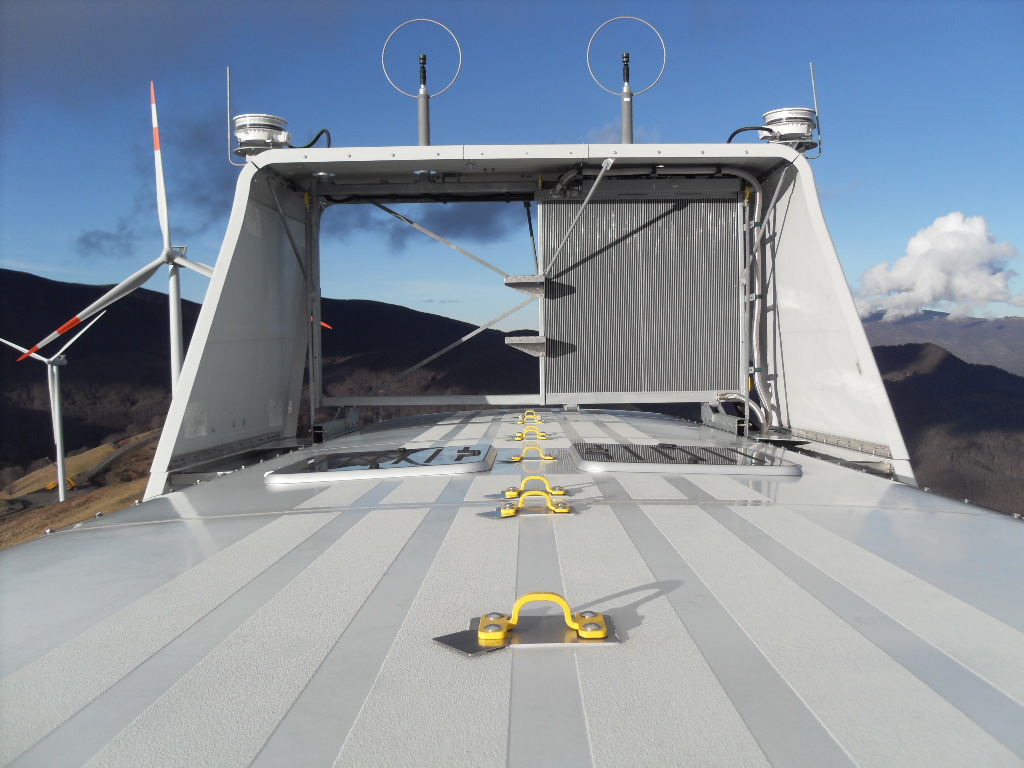

Instead, to have an idea of how harsh life was in these areas, you can follow the old mule tracks of the transhumance. Taking the best known stretch from the village of Noce, you can reach the ridges of Mount Rosso arriving at Formentara, an old alpine farmhouse with a “piagne” roof (sandstone tiles), the typical stone of the Lunigiana. Dating from the 16th century, it is now deserted, but until the fifties it was a camp for the transhumance shepherds, who journeyed here in the good seasons with their sheep and remained until the end of November, when it was time to go back down into the valleys. Near the village, there is a dirt road that takes you to Mount Colombo, where we find the wind farm, or you can rejoin the main road and arrive at the Due Santi Pass, where there is the Zum Zeri ski area between Granducato di Toscana and Ducato di Parma. From here, the view of the Gulf of La Spezia and the Cinque Terre is truly spectacular.

Agricultural excellence

In this area, the acknowledged product of excellence is, of course, Zeri lamb, certified by Slow Food. It is a locally-bred ovine, the zerasca, living in the wild, quite recognizable due to its large horns. “It is a very particular species of the Apennine sheep, in danger of extinction”, tells Cinzia Angiolini of Slow Food, who together with other livestock farmers created, in the early 2000s, a consortium to promote Zeri sheep and lamb. She would have been content to paint them but, instead, ended up becoming a shepherdess.

You can easily see her on the roadside between La Dolce and Rossano, conversing with her animals. She has 380. Some, the older ones, inherited from her father’s farm, she still calls by name – Adelina, Natalina, Filippa. The lamb meat of Zeri is considered especially tasty. Lean, sweet, aromatic but without any gamey traces. In keeping with the traditions here, the lamb is cooked in testi – a sort of cast iron portable oven (at one time in terracotta) – shaped like a low wide pot placed over a fire made from wood bundles and hot coals. A slow and long process, that is well-suited to the silence of these mountainous lands.

Villages to visit

The classic image of Lunigiana, a little postcard-like, is of a village perched at the foot of a castle that dominates the valley. Therefore, once here, it is worth at least a day to wander through the villages of this land of mountain passes. Amongst the more interesting villages, Fivizzano is certainly worth visiting. Renamed the “Athens of the Lunigiana”, due to a story of ancient humanistic tradition. This village, at one time, had been a coach stop along the Via Nuova Clodia, and you can still see the walls commissioned by Cosimo de’ Medici, and where Jacopo da Fivizzano from 1470 to 1474 set for the first time the font to be used to print the texts of Giovenale, Virgilio and Cicerone, before cities, such as Vienna or Oxford. As well, in Fivizzano, in the early 19th century, Agostino Fantoni invented the first typewriter. The Museo della Stampa, located inside Palazzo Fantoni Bononi, pays homage to the ties between Lunigiana and printing.

City of the book

Speaking of books. In Lunigiana, there is the small locality of Montereggio (Municipality of Mulazzo) which today is known as the town of books – the only Italian town included on the World List of Book Towns, and has a fascinating story to be told. In 1815, its inhabitants, hit by a serious agricultural crisis, in order to survive became itinerant booksellers. They were illiterate, recognizing the books by their colors and pictures, but this did not stop them from heading out with panniers loaded with books visiting towns and cities across the center and north of Italy. This trade, at the beginning little more than a way to survive, expanded during the Risorgimento, when some of them became almost smugglers, bringing from France Carbonari books prohibited by the Austrian censure. With the passing of time, in the early 20th century, some booksellers began to establish themselves in the town, first selling from street stalls (from this, the famous Bancarella Prize, awarded to booksellers), and then setting up bookshops. Nowadays, the village, whose streets are named after the great Italian publishers, has a population of 20 or so individuals. It becomes lively again in August when the “Festa del Libro” (what else?) is held. However, in the north of Italy, there are still booksellers who carry the names of those early families.

A look towards the sea

To bring the circle to a close, and end this long editorial-literary journey, nothing remains but to head towards the sea, in the direction of the Gulf of the Poets, where in the second half of the fifties there occurred the most extraordinary Italian retreat of the 20th century. In Lerici, in the old part of the town, Valentino Bompiani had a house, a villa that had numerous appendages added to it and where an entire community was housed, amongst others, many writers, from Moravia to Eco. From here, after a little less than 4 kilometres, in the little village of Tellaro, which overlooks the sea, we find the home of Mario Soldati. The Piedmontese writer arrived here following in the steps of an elusive travelling trunk of Lawrence’s which was purported to have contained who knows what unpublished manuscripts. Of course, he was never able to find it, but Soldati fell in love with the place that then you could only reach by sea and never left.

The last stage of the triptych brings us to Bocca di Magra, a small village on a river that in the sixties became a favourite refuge of intellectuals. A type of Einaudian fiefdom, where you could have encountered Vittorio Sereni writing poetry under a pine tree, Vittorini eating at the famous tavern of Sans Façon or Mary McCarty on the river’s bank absorbed in composing a letter to her friend Hannah Arendt. The group of writer friends also tried to have a town plan approved, drawn up by the architect Giancarlo De Carlo (father of the writer Andrea) to block the first attempts at speculation, but in vain. The wicked irony of Luciano Bianciardi was ferocious in the form of a rhyme. It began: “Arise, my friends! In a horde, let’s defend the cliffs!”.